This is a blog post about my graduation project, where I went for a little dive within the scary realm of AI. I had zero practical experience with AI prior and had only a minimal theoretical understanding of some concepts. While this work may not seem like much, this was a rough ride for me, and I can confidently say that it was worth it. I couldn’t have had the opportunity to do this type of work otherwise, and I will probably not touch AI at this level anytime soon. This is basically a brain dump of some of my thoughts, including an explanation of my project so I can have some peace of mind and move on.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence has been prevalent lately. This can be accounted for many reasons, but the most important is Moore’s Law. The amount of compute power available to the average user, let alone big corporations such as Microsoft and Facebook, is way more than what we could get in the ’90s.

This becomes clear when we observe the nature of the current state-of-the-art trends in AI. The Transformer model, which was proposed by Vaswani et al. in 2017, rids of any feedback connections (RNNs) and only utilizes what they called “self-attention”. This operation is highly parallelizable and can exploit the large number of cores in modern GPUs.

Overview of the project

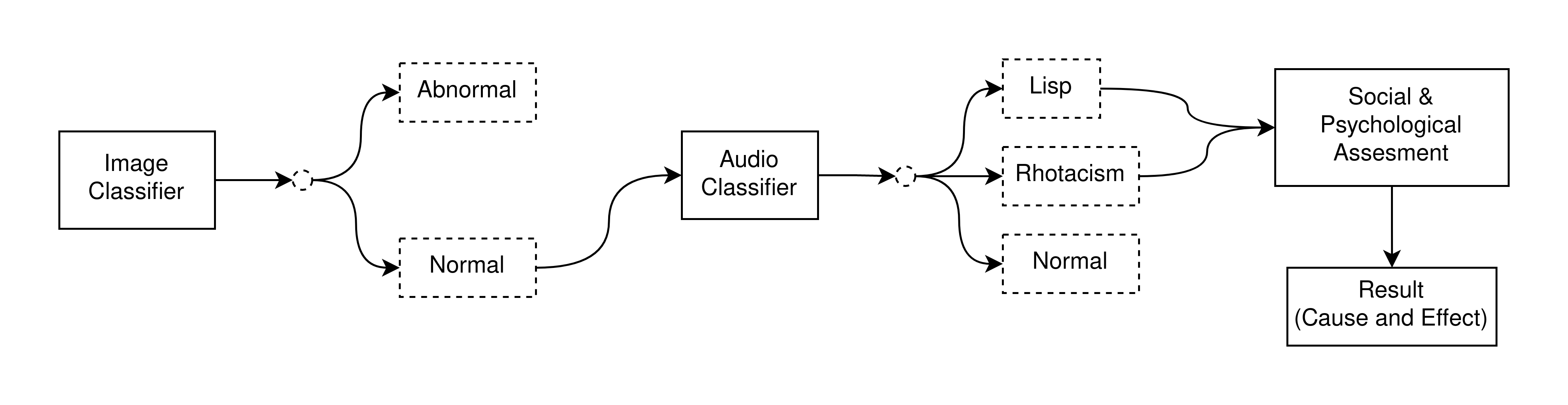

Our project addresses the problem of articulation disorder diagnosis in the Arabic language. We take a multimodal approach to solve this problem. We first identify whether the disorder is of a physiological nature or not. This is achieved through a binary image classifier that is trained on public pictures of patients with a hare lip. We only chose hare lip for our prototype due to its abundance of data.

Once the patient has been classified to have an abnormality, we do nothing further. On the other hand, if the patient doesn’t have a physiological disorder, then we proceed to the second stage of the pipeline, which is the audio analysis phase. In this phase, the patient utters multiple words into a microphone that feeds into our AI model to further classify the patient’s articulation disorder (Lisp, Rhotacism, …). The model was trained on data that we gathered locally.

After the articulation disorder has been classified, the patient undergoes a written questionnaire that identifies whether the disorder could be due to psychological or social reasons.

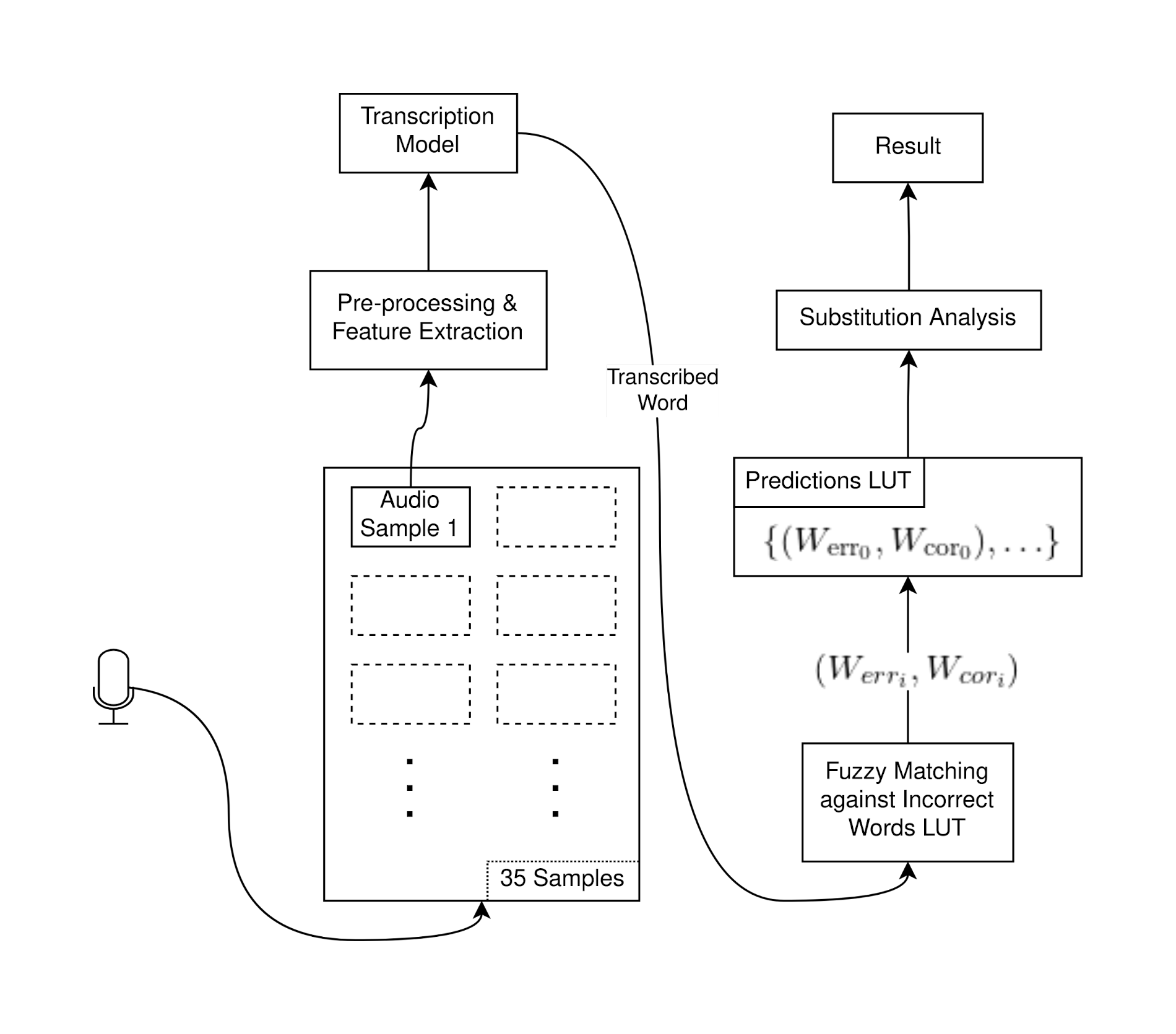

The following picture shows an overview of the first experiments with the project. At a later stage in our project, we improved the audio pipeline by utilizing a transformer-based approach that performs Automatic Speech Recognition. This replaced the LSTM audio classification pipeline.

I will focus on the audio pipelines in this blog post. The image pipeline was the work of my friend Mostafa, while the questionnaire was the work of Seif.

NLP in AI and History

NLP has been a target of AI for a very long time. In the following paragraphs, we will go through some of the history to get a better context on what we are currently targeting.

Natural languge can be expressed in two main forms

- Text form

- Audio form

Both of these forms have one thing in common: their output depends on past input. Modeling this type of system is tricky. We need a model that can represent this causal relationship between input and output.

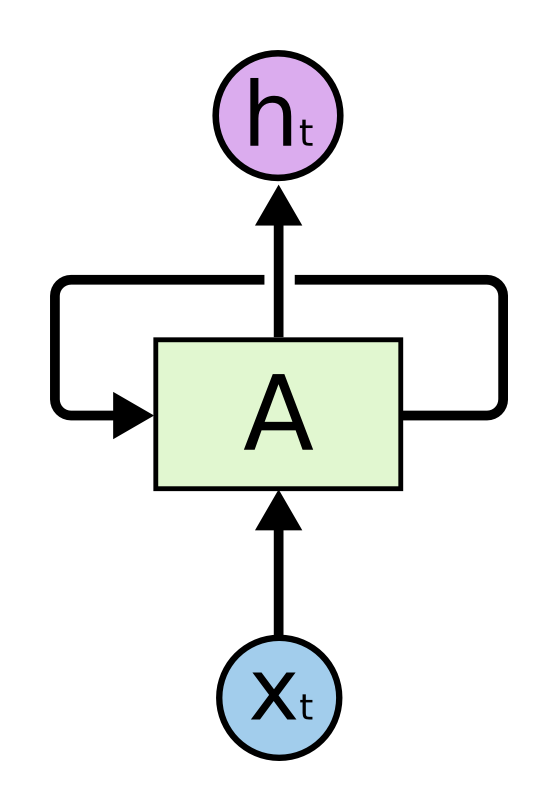

This is where we start using the recurrent neural network to model our data. The RNN is a type of neural network that has feedback. This is necessary to model natural language since the network’s output depends on past input.

This network architecture proved to be problematic when dealing with very large data sizes. This is due to the failure of the model to capture information that is far away from the current word due to the vanishing gradient problem.

In 1997, a research paper was published that introduced a new RNN architecture called the “Long Short-Term Memory” (LSTM). This architecture dealt with the vanishing gradient problem by introducing a gating mechanism inside the cells of the network. This enables us to control the gradient flow within the cell so we can prevent the gradient from vanishing or exploding.

Up to this point, we could use LSTMs to predict new data from past data. However, we had always struggled with sequence-to-sequence learning. This was a very special task in NLP that involved transforming an input sequence to an output sequence. The most popular sequence-to-sequence task is machine translation, where we transform a sequence of words in a certain language to another sequence of words in another language.

In 2014, researchers from Google published a paper that proposed a new network architecture that could deal with sequence-to-sequence tasks: The encoder-decoder architecture.

The idea is to use one LSTM, the encoder, to read the input sequence one timestep at a time, to obtain a large fixed dimensional vector representation (a context vector), and then to use another LSTM, the decoder, to extract the output sequence from that vector. The second LSTM is essentially a recurrent neural network language model except that it is conditioned on the input sequence.1

Beyond LSTMs: Attention and Transformers

However, even though LSTMs could now capture longer dependencies and perform Seq2Seq tasks, they still struggled with retaining information for very long sequences. This was mainly due to the limited memory of LSTMs and their noise accumulation.

In 2014, a research intern at Montreal University published a paper where he proposed a new way to approach neural machine translation, addressing the limitation of the fixed-length context vector in the encoder-decoder architecture. Instead of relying solely on the final hidden state of the encoder, the attention mechanism allows the decoder to adaptively focus on different parts of the input sequence while generating the output sequence. This is done by learning a set of alignment weights between the input and output sequences. He called this new mechanism “Attention” and achieved state-of-the-art translation performance with his architecture.

Everything up to this point still used LSTMs, which wasn’t all that great. We can observe that all the innovation that was done in 2014 was huge, and it started adding components to the LSTM: a component for the encoder and decoder, and another component for the attention mechanism. All of this was built on top of the trusty old LSTMs from the ’90s.

Three years into the future and we are now in 2017. Eight researchers from Google Brain published a disruptive paper in the field of AI. They proposed yet another new architecture that didn’t build upon the LSTM, as we have seen lately. Instead, it stripped the LSTM component entirely from the network architecture, keeping the encoder-decoder structure and the attention mechanism. They named the paper “Attention is All You Need,” in which they introduced the “Transformer” architecture.

It didn’t just solve the problem of representing longer sequences; it also was a beast of transfer learning, unlike the LSTMs. One can take a general-purpose transformer and fine-tune it with so little data to achieve state-of-the-art results in their specialized application.

This also meant that we no longer have to train models from scratch each time we need to solve a specific problem. If there’s a transformer model that can deal with the problem even at a general level, probably fine-tuning is the way to go. This became very popular in the field of Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) systems. We started witnessing big transformer models trained on decades of audio data that people fine-tuned for their specific use case or language.

Back to the present: LSTMs

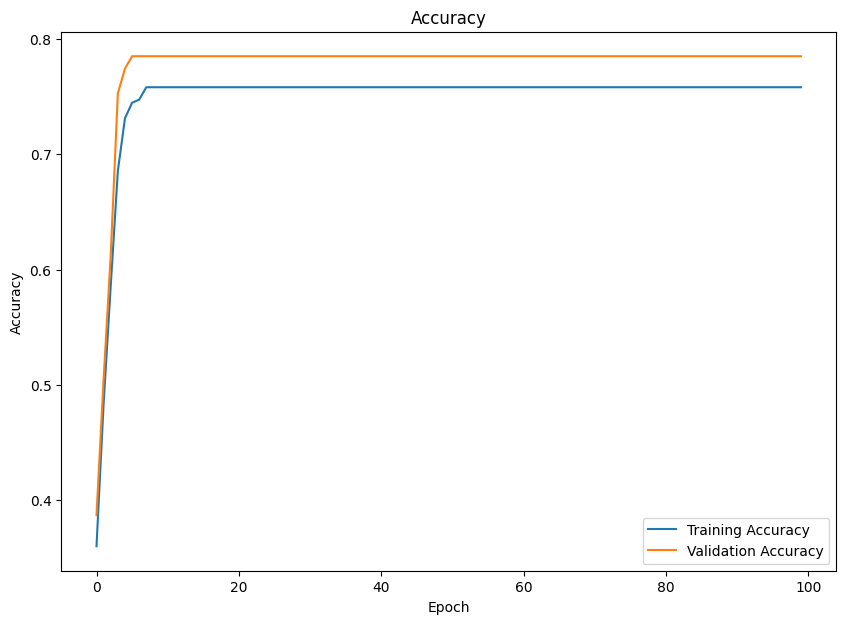

I’m going to quickly go over our experiments with training an LSTM classifier for our problem. We had three classes of articulation disorders:

- Lisp

- Rhotacism

- No Disorder

We wanted a model to identify the disorder from an audio sample (an uttered word in audio form). We had no data and couldn’t find any Arabic audio data of children with articulation disorders online, so we started gathering data manually. We approached local medical centers and nurseries. After dealing with a lot of trouble trying to explain the project, getting consent from parents, and setting up our equipment, we started gathering data.

Tedious days of data gathering went by. Initially, we had around 2 hours of raw recordings. Then came cleaning, which was followed by labeling, which we split amongst our team. We ended up with around 15 minutes of audio data :loudly_crying_face:. This seemed so little, but we kept going anyway.

We kept experimenting with different model hyperparameters on our dataset, but every single try showed a sign of overfitting. It became clear that we could no longer progress further with the little data that we have, and hence we started with plan B.

Plan B: Transformers

I was always interested in transformers. I was initially planning to fine-tune a transcription model like Whisper by OpenAI on the little data that I have, but I was very skeptical it would make any difference fine-tuning such a huge model on my 15 minutes of data.

I was chatting about this Whisper fine-tuning dilemma with my friend Mohey (he’s the AI expert I know 🧠) when he suggested I just transcribe the audio with the Whisper model and transform my classification problem to just an audio transcription problem. This was basically the beginning of the end for my graduation project.

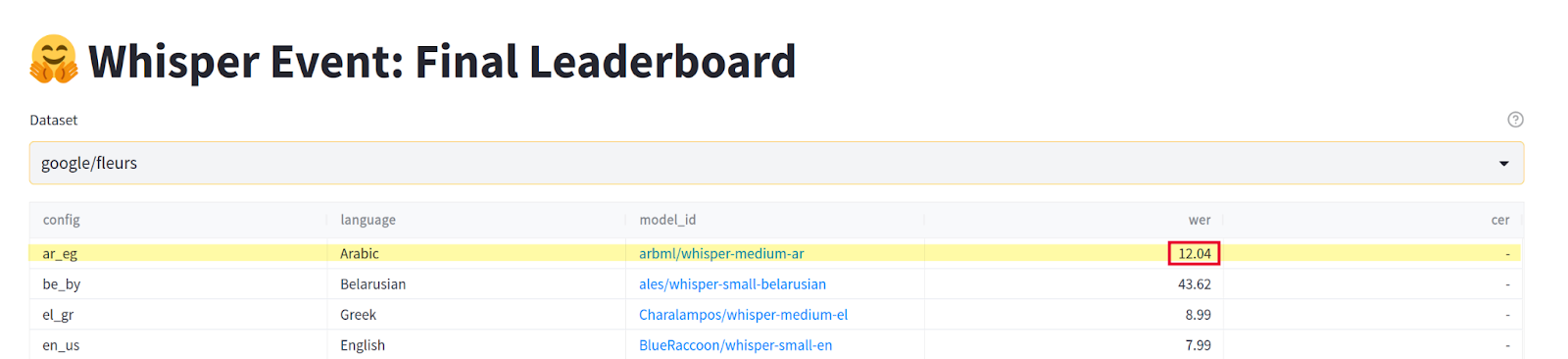

After looking around for the hottest fine-tuned models for the Arabic language, I saw the amazing work of ArabML in the Whisper fine-tuning event by Hugging Face. They had fine-tuned a model that achieved a WER of 12.04, and it was on an Arabic dataset of the Egyptian dialect. That was exactly what I needed, so I started experimenting with the model through the free Hugging Face inference API. It didn’t transcribe the incorrect words very accurately, most likely due to word normalization that is associated with automatic speech recognition (ASR) models, but it was something I could work with.

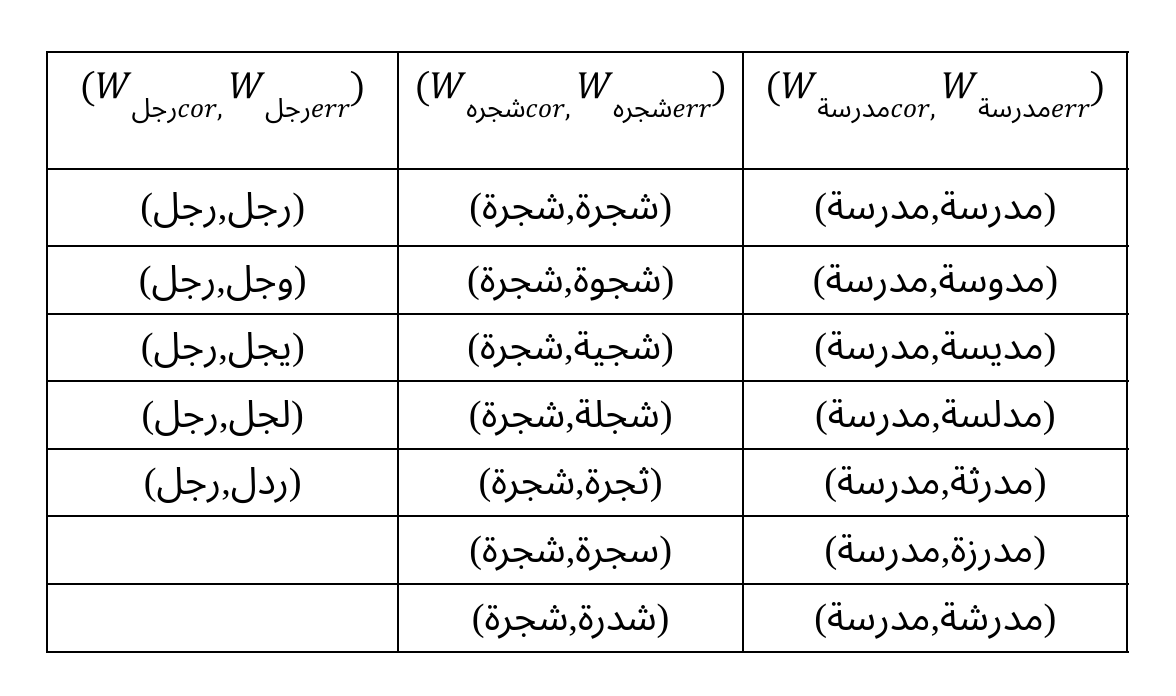

I created a list of all the possible wrong words (that have articulation errors) that we could face along with the corresponding correct words, as shown in the image below.

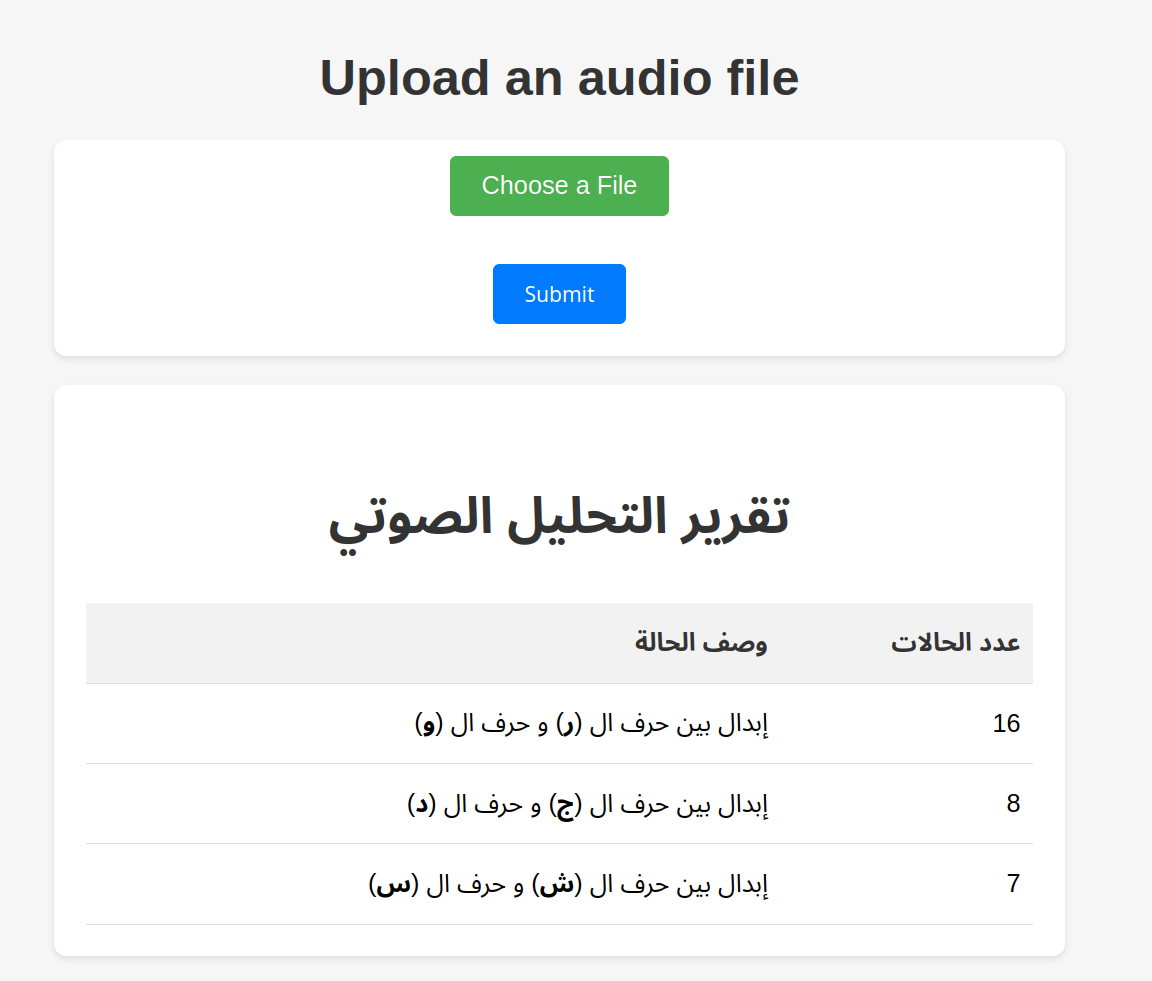

After creating this list, we just feed the transcribed text to an algorithm that can find the closest match from our words list. This process is repeated for all the uttered words, and we have a list of all the wrong words that were uttered along with their corresponding correct word. The letter difference between these two words will be the substituted letter.

This pipeline was implemented in Python with a simple Flask frontend. You can find all the corresponding code in my GitHub repo MAD-Whisper.

Special Thanks

I would like to thank everyone who has helped me with this small research project, and especially my team for being such strong supporters during our journey. I am also grateful for their patience with my frequent tantrums throughout the past year, so a huge thanks go to both Mostafa and Seif!

Additionally, I would love to thank Mohey for being an awesome, well-rounded nerd. Credit goes to him for the crazy ASR transformer idea. I truly enjoyed our discussions and learned a lot from them.

Thanks to ARABML community for their astounding open-source research, and specifically their whisperar initiative and models which I have used within my project.

Finally, thanks to our project advisor, Dr. Mohamed Safy, for supporting our project and for connecting us with medical specialists whom we consulted during our project.

Bonus

excerpt from my presentation